A recent Forbes India article discusses PepsiCo India’s new chairman, Manu Anand’s, strategy for developing a business model that better reaches BOP consumers. Though the company made a concerted effort to develop a plan for long-term growth in India a few years ago, it has taken time to understand consumer needs and distribution strategies. With a continuously evolving model, the strategies Anand is implementing focuses on greater incentives and higher margins for distributors and shopkeepers in slums and rural areas. Shopkeepers for instance, receive an incentive to recommend a particular PepsiCo product to customers. They are also extended credit to be able to purchase products from PepsiCo. The company is also employing a low-cost sales model, which relies on field salesmen.

How PepsiCo India’s new chairman Manu Anand is tearing down existing rules to create an exciting new business model to serve bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers

Santosh Nagar is almost a city within a city. Inside this sprawling slum in Mumbai’s north-western suburbs are rows of houses that sit cheek by jowl with each other. Over 20,000 residents run businesses from tailoring to soap making in its narrow, labyrinthine bylanes. There are almost half a dozen schools and hawkers selling everything from brooms to insurance policies. Not to forget the ubiquitous kirana store, one every 15 metres, serving a growing demand for everyday household items, from mosquito coils to popular detergent, from lanterns to shampoo sachets.

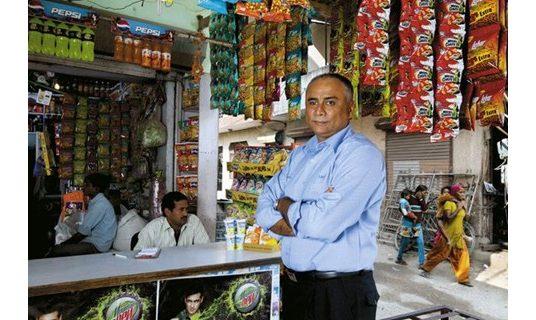

Ravi Maurya, whose tuck shop lies amid this hustle-bustle, has been doing brisk business in this urban slum for a quarter of a century. Maurya wouldn’t think of moving out of Santosh Nagar. This is where he’s always lived — and earned his livelihood, serving countless customers, many of whom transact no more than Rs. 5 at a time. Maurya’s merchandise is also tailored accordingly — small pack sizes, lower priced products and lesser known brands. The national brands that get advertised on television don’t always make it to Maurya’s shop shelf, unless he decides to go to the local wholesaler and buy his supplies. The large company distributors shun stores like his situated inside the slum, preferring to restrict themselves to the larger outlets, about a kilometre or two away. “They just didn’t care about us,” says Maurya.

So about a year ago, Maurya was pleasantly surprised when a PepsiCo distributor salesman turned up at his door, offering to book orders, supply ready stock and even offer him a week’s credit. As a result, today PepsiCo’s Lehar range of namkeens and wafers hang from shop fronts in his store — and across most of Santosh Nagar — aggressively competing with locally made brands like Diamond and Balaji.

Lehar’s arrival inside the bylanes of large urban slums like Santosh Nagar represents just one part of the $60 billion (global net revenue) PepsiCo’s larger push to build a significant business catering to the consumers at the bottom-of-the-pyramid (BoP) in India. About three years ago, PepsiCo drew up a new blueprint for long-term growth in India. It spoke of the need for significantly widening reach, aiming for the new consuming class across urban and rural India — and more importantly, creating a whole new set of locally developed products for the masses.

Till then, PepsiCo’s attempts to push deeper into the Indian heartland had entailed introducing smaller pack sizes of its wafers and smaller glass bottles of Pepsi cola priced at Rs. 5. But somehow, that didn’t help widen the consumer base for wafers and beverages. It realised it needed a completely different approach to serve BoP consumers. It discovered two routes: Its joint venture with Tata Global Beverages to launch affordable health drinks and also completely reworking the Lehar business model to connect with a wider consumer base.

Starting a year-and-a-half ago, under its chairman Sanjeev Chadha’s leadership in India, it began a series of experiments with product concepts that were tailored for BoP consumers. At least two such concepts have already been successfully tested. One of them is Lehar Iron Chusti, a range of iron fortified biscuits and puffs, targeted at adolescent girls, priced at Rs. 2. It was tested in Guntur in Andhra Pradesh. And across rural Maharashtra and Gujarat, through its joint venture with Tata GlucoPlus, a lemon drink, priced at about Rs. 6, with isotonic salts and rehydration capabilities being marketed to urban labourers and rural agricultural workers.

Around the time Manu Anand took over from Chadha as the new chairman a year ago, these pilots were being rolled out. Both turned out to be successful. So the real issue now was how to take them to the market and build a profitable business that also had scale. Anand, who’s been with PepsiCo for 18 years, was among the first employees in the fledgling foods division in India. He was witness to two failed attempts at building a foods business in the past. The foods division had to literally fight for attention and resources with a much larger beverage business. “I had a boss in Thailand who had difficulty understanding what I was doing,” Anand says, pointing to the fact that selling foods in India is an entirely different ball game.

In 1999, Kurkure’s unexpected success — Anand was then the MD of Frito-Lay India — changed things and grabbed the attention of PepsiCo’s global bosses. Yet even Anand acknowledges the fact that the Lehar brands of namkeens and bhujiyas being part of the larger foods division did not get the attention it should have. He left the Indian operations in 2007, and was the Business Unit General Manager for South East Asia until 2010. Today, he is back at a time when the beverage and snack-foods businesses have been combined together. Anand is now trying to figure out a whole new BoP business model that allows PepsiCo to take on the local halwai — while leveraging the scale and technology that its business already has.

Not business-as-usual

The clues lie inside the Lehar Foods office building in Gurgaon, a far cry from the swanky Global Business Park office a couple of kilometres away where the rest of the PepsiCo employees sit. There are paan stains on the stairs. The walls have cheap whitewash. The corridors aren’t air-conditioned and the lifts are in a shabby condition. Real estate agents in the area reckon rents here are about half that of the Global Business Park.

Knocking out needless overheads is part of Anand’s plan to take on the local halwai. And it started by spinning out the Lehar foods business as a separate profit centre from the larger foods team. “Manu was very firm that there are clear guard rails on each of the businesses and this would have to be treated differently. We didn’t want the shadow of an existing business coming over them,” says Varun Berry, chief executive, foods at PepsiCo India. A separate team of 30 employees out of the total 2,000-strong foods division was formed under this profit centre and given clear sales targets.

Compensation structures were also rejigged, with variable pay about a third higher than their colleagues in other parts of the company. The lean structure was based on smart outsourcing of every element of cost.

Manufacturing was another area where costs were cut down. So far Pepsi had only three manufacturing plants in the country for Lays, a potato-based product. It was not easy to produce as potatoes had to be refrigerated for long periods and handled delicately. What this did was add tremendous freight costs to the final cost of the product.

On the other hand, the namkeens that Lehar Foods produced were a lot easier to make. Technologically, all it required was an entrepreneur who could roll dough, fry and pack it. Importantly for the company, it did not have to invest in plant and equipment. Once it decided to adopt the co-pack model, freight costs reduced by half. Company insiders say that the long-term aim is to have a co-packer every 200 kilometres across India. Packaging materials were also looked at closely.

An entirely new distribution model was laid out. Unlike brands like Quaker Oats, Tropicana and Lays, where advertising plays a role in driving demand, these products would receive no advertising support and be sold more on the ‘push model’, where the shopkeeper is given an incentive to recommend the product to customers.

Sampling is encouraged and distributor agents fan out across outlets to persuade them to stock company products on their shelves. They’ve pushed deeper into cities into slum bylanes that they would never have thought of servicing before. In Mumbai’s Santosh Nagar slum, Lehar products compete with local upstart brands like Diamond Chips and Balaji Wafers.

However, competition is tough, according to a distributor who declined to be identified. Local competitors are much faster at reacting to changes in the marketplace, he says. Shopkeepers agree. They cite the example of Diamond Chips that has caught the fancy of young children by offering a free tattoo with every pack.

PepsiCo also worked at understanding a low-cost distribution model. Both the shopkeeper and distributor are given higher margins. For instance, the kirana store gets 80 paisa on every Rs. 5 pack of Lehar namkeen sold. It gets 75 paisa on a Rs. 10 pack of Lays chips. Sometimes, shopkeepers also get a longer credit period.

But unlike its normal distribution channel, where PepsiCo is investing in handhelds, this new distribution relies on field salesmen who from move shop to shop collecting cash and distributing products. PepsiCo has made no investment in the network. It is the distributor who has put money upfront. Distributor salesmen sell products worth about Rs. 15,000 a day and earn about Rs. 1,000 a day, according to a sales expert based in Mumbai.

Understanding the BoP consumer

Before it worked on the business model, PepsiCo realised that to succeed with the bottom of the pyramid customers, it first had to have the right products in place. Its existing products weren’t seen as up to the task and research teams fanned out across small town and rural India.

One of the questions PepsiCo had constantly asked internally for years was why bottom of the pyramid consumers hardly drank any beverage. After all, they used soaps and shampoos so why not drink beverage in smaller pack sizes? What emerged was that the reason they did not consume was as much affordability as it was relevance. Users in this class wanted a clear utility proposition. With soaps and shampoos, the utility was clearly established. An overwhelming majority said that their occupations required a lot of hard work and they wanted a beverage that not only refreshed them, but recharged them.

Once the proposition was clear, the company went about creating a “Gatorade (its popular sports drink around the world) that cost very little, but had Gatorade-like qualities.” Similarly, the team came up with the finding that adolescent girls in small town India often suffered from iron deficiency. If not fixed at that age it could linger for many years. “As you hit the sweet spot, the scale up happens very fast and it doesn’t stop at one product — you have the whole range,” says Anand.

Lehar Iron Chusti was made to address a very specific need — iron deficiency in adolescent girls. Its existing range of Lehar namkeens were to be sold in smaller pack sizes as a belly fill. Here the team worked on flavours to appeal to different palettes across India. Today, the company comes up with a new flavour every month.

Over the last nine months, Pepsi has also undertaken its first tentative steps at crafting a go-to-market strategy. Once the team came up with Lehar Iron Chusti, the challenge was centred on marketing. Simply putting the biscuit in stores would not work, nor would its budget support advertising costs.

In Andhra Pradesh’s Guntur and Tenali, the company went about an arduous door-to-door marketing. As a first step, the company appointed change agents to go from house to house to explain what iron deficiency is to mothers. Shyamala, a change agent, says the company soon discovered that the biggest shopping occasion is after school and the focus soon shifted to schools.

Pavanasahiti, a ninth standard student, says as a result of the information she received, her mother started feeding her spinach. Change agents say the hope is that students like Pavanasahiti will, in time, start buying other Lehar products. In developing more bottom-of-the-pyramid products PepsiCo says it has seen that rural consumers are not keen to experiment with different tastes. So while Iron Chusti comes with a tangy taste in the south, if it were to be launched in say the north, it would have a more spicy flavour.

Iron Chusti is sold in small towns with a population of less than 2,000 through rural entrepreneurs who go from village to village. Travelling on a bicycle, K. Nagendra covers 18 villages a week. His sole mandate: To get Iron Chusti into as many outlets as possible. He’s paid Rs. 1,500 as a retainer and makes as much as three times more in incentives. “I’m my own boss. I don’t feel like I’m working for anyone,” says Nagendra.

Back in the PepsiCo offices in Gurgaon, Anand is working on creating the same entrepreneurial culture at his Lehar Foods team. For starters, he’s banned PowerPoint presentations at review meetings. Executives are expected to come into his office with their plans on simple work sheets and walk out with clear decisions. Its early days, but Anand says the performance of its bottom-of-the-pyramid businesses have been encouraging. “We’ve got to keep innovating and see what sticks,” he says.How PepsiCo India’s new chairman Manu Anand is tearing down existing rules to create an exciting new business model to serve bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers

Santosh Nagar is almost a city within a city. Inside this sprawling slum in Mumbai’s north-western suburbs are rows of houses that sit cheek by jowl with each other. Over 20,000 residents run businesses from tailoring to soap making in its narrow, labyrinthine bylanes. There are almost half a dozen schools and hawkers selling everything from brooms to insurance policies. Not to forget the ubiquitous kirana store, one every 15 metres, serving a growing demand for everyday household items, from mosquito coils to popular detergent, from lanterns to shampoo sachets.

Ravi Maurya, whose tuck shop lies amid this hustle-bustle, has been doing brisk business in this urban slum for a quarter of a century. Maurya wouldn’t think of moving out of Santosh Nagar. This is where he’s always lived — and earned his livelihood, serving countless customers, many of whom transact no more than Rs. 5 at a time. Maurya’s merchandise is also tailored accordingly — small pack sizes, lower priced products and lesser known brands. The national brands that get advertised on television don’t always make it to Maurya’s shop shelf, unless he decides to go to the local wholesaler and buy his supplies. The large company distributors shun stores like his situated inside the slum, preferring to restrict themselves to the larger outlets, about a kilometre or two away. “They just didn’t care about us,” says Maurya.

So about a year ago, Maurya was pleasantly surprised when a PepsiCo distributor salesman turned up at his door, offering to book orders, supply ready stock and even offer him a week’s credit. As a result, today PepsiCo’s Lehar range of namkeens and wafers hang from shop fronts in his store — and across most of Santosh Nagar — aggressively competing with locally made brands like Diamond and Balaji.

Lehar’s arrival inside the bylanes of large urban slums like Santosh Nagar represents just one part of the $60 billion (global net revenue) PepsiCo’s larger push to build a significant business catering to the consumers at the bottom-of-the-pyramid (BoP) in India. About three years ago, PepsiCo drew up a new blueprint for long-term growth in India. It spoke of the need for significantly widening reach, aiming for the new consuming class across urban and rural India — and more importantly, creating a whole new set of locally developed products for the masses.

Till then, PepsiCo’s attempts to push deeper into the Indian heartland had entailed introducing smaller pack sizes of its wafers and smaller glass bottles of Pepsi cola priced at Rs. 5. But somehow, that didn’t help widen the consumer base for wafers and beverages. It realised it needed a completely different approach to serve BoP consumers. It discovered two routes: Its joint venture with Tata Global Beverages to launch affordable health drinks and also completely reworking the Lehar business model to connect with a wider consumer base.

Starting a year-and-a-half ago, under its chairman Sanjeev Chadha’s leadership in India, it began a series of experiments with product concepts that were tailored for BoP consumers. At least two such concepts have already been successfully tested. One of them is Lehar Iron Chusti, a range of iron fortified biscuits and puffs, targeted at adolescent girls, priced at Rs. 2. It was tested in Guntur in Andhra Pradesh. And across rural Maharashtra and Gujarat, through its joint venture with Tata GlucoPlus, a lemon drink, priced at about Rs. 6, with isotonic salts and rehydration capabilities being marketed to urban labourers and rural agricultural workers.

Around the time Manu Anand took over from Chadha as the new chairman a year ago, these pilots were being rolled out. Both turned out to be successful. So the real issue now was how to take them to the market and build a profitable business that also had scale. Anand, who’s been with PepsiCo for 18 years, was among the first employees in the fledgling foods division in India. He was witness to two failed attempts at building a foods business in the past. The foods division had to literally fight for attention and resources with a much larger beverage business. “I had a boss in Thailand who had difficulty understanding what I was doing,” Anand says, pointing to the fact that selling foods in India is an entirely different ball game.

In 1999, Kurkure’s unexpected success — Anand was then the MD of Frito-Lay India — changed things and grabbed the attention of PepsiCo’s global bosses. Yet even Anand acknowledges the fact that the Lehar brands of namkeens and bhujiyas being part of the larger foods division did not get the attention it should have. He left the Indian operations in 2007, and was the Business Unit General Manager for South East Asia until 2010. Today, he is back at a time when the beverage and snack-foods businesses have been combined together. Anand is now trying to figure out a whole new BoP business model that allows PepsiCo to take on the local halwai — while leveraging the scale and technology that its business already has.

Not business-as-usual

The clues lie inside the Lehar Foods office building in Gurgaon, a far cry from the swanky Global Business Park office a couple of kilometres away where the rest of the PepsiCo employees sit. There are paan stains on the stairs. The walls have cheap whitewash. The corridors aren’t air-conditioned and the lifts are in a shabby condition. Real estate agents in the area reckon rents here are about half that of the Global Business Park.

Knocking out needless overheads is part of Anand’s plan to take on the local halwai. And it started by spinning out the Lehar foods business as a separate profit centre from the larger foods team. “Manu was very firm that there are clear guard rails on each of the businesses and this would have to be treated differently. We didn’t want the shadow of an existing business coming over them,” says Varun Berry, chief executive, foods at PepsiCo India. A separate team of 30 employees out of the total 2,000-strong foods division was formed under this profit centre and given clear sales targets.

Compensation structures were also rejigged, with variable pay about a third higher than their colleagues in other parts of the company. The lean structure was based on smart outsourcing of every element of cost.

Manufacturing was another area where costs were cut down. So far Pepsi had only three manufacturing plants in the country for Lays, a potato-based product. It was not easy to produce as potatoes had to be refrigerated for long periods and handled delicately. What this did was add tremendous freight costs to the final cost of the product.

On the other hand, the namkeens that Lehar Foods produced were a lot easier to make. Technologically, all it required was an entrepreneur who could roll dough, fry and pack it. Importantly for the company, it did not have to invest in plant and equipment. Once it decided to adopt the co-pack model, freight costs reduced by half. Company insiders say that the long-term aim is to have a co-packer every 200 kilometres across India. Packaging materials were also looked at closely.

An entirely new distribution model was laid out. Unlike brands like Quaker Oats, Tropicana and Lays, where advertising plays a role in driving demand, these products would receive no advertising support and be sold more on the ‘push model’, where the shopkeeper is given an incentive to recommend the product to customers.

Sampling is encouraged and distributor agents fan out across outlets to persuade them to stock company products on their shelves. They’ve pushed deeper into cities into slum bylanes that they would never have thought of servicing before. In Mumbai’s Santosh Nagar slum, Lehar products compete with local upstart brands like Diamond Chips and Balaji Wafers.

However, competition is tough, according to a distributor who declined to be identified. Local competitors are much faster at reacting to changes in the marketplace, he says. Shopkeepers agree. They cite the example of Diamond Chips that has caught the fancy of young children by offering a free tattoo with every pack.

PepsiCo also worked at understanding a low-cost distribution model. Both the shopkeeper and distributor are given higher margins. For instance, the kirana store gets 80 paisa on every Rs. 5 pack of Lehar namkeen sold. It gets 75 paisa on a Rs. 10 pack of Lays chips. Sometimes, shopkeepers also get a longer credit period.

But unlike its normal distribution channel, where PepsiCo is investing in handhelds, this new distribution relies on field salesmen who from move shop to shop collecting cash and distributing products. PepsiCo has made no investment in the network. It is the distributor who has put money upfront. Distributor salesmen sell products worth about Rs. 15,000 a day and earn about Rs. 1,000 a day, according to a sales expert based in Mumbai.

Understanding the BoP consumer

Before it worked on the business model, PepsiCo realised that to succeed with the bottom of the pyramid customers, it first had to have the right products in place. Its existing products weren’t seen as up to the task and research teams fanned out across small town and rural India.

One of the questions PepsiCo had constantly asked internally for years was why bottom of the pyramid consumers hardly drank any beverage. After all, they used soaps and shampoos so why not drink beverage in smaller pack sizes? What emerged was that the reason they did not consume was as much affordability as it was relevance. Users in this class wanted a clear utility proposition. With soaps and shampoos, the utility was clearly established. An overwhelming majority said that their occupations required a lot of hard work and they wanted a beverage that not only refreshed them, but recharged them.

Once the proposition was clear, the company went about creating a “Gatorade (its popular sports drink around the world) that cost very little, but had Gatorade-like qualities.” Similarly, the team came up with the finding that adolescent girls in small town India often suffered from iron deficiency. If not fixed at that age it could linger for many years. “As you hit the sweet spot, the scale up happens very fast and it doesn’t stop at one product — you have the whole range,” says Anand.

Lehar Iron Chusti was made to address a very specific need — iron deficiency in adolescent girls. Its existing range of Lehar namkeens were to be sold in smaller pack sizes as a belly fill. Here the team worked on flavours to appeal to different palettes across India. Today, the company comes up with a new flavour every month.

Over the last nine months, Pepsi has also undertaken its first tentative steps at crafting a go-to-market strategy. Once the team came up with Lehar Iron Chusti, the challenge was centred on marketing. Simply putting the biscuit in stores would not work, nor would its budget support advertising costs.

In Andhra Pradesh’s Guntur and Tenali, the company went about an arduous door-to-door marketing. As a first step, the company appointed change agents to go from house to house to explain what iron deficiency is to mothers. Shyamala, a change agent, says the company soon discovered that the biggest shopping occasion is after school and the focus soon shifted to schools.

Pavanasahiti, a ninth standard student, says as a result of the information she received, her mother started feeding her spinach. Change agents say the hope is that students like Pavanasahiti will, in time, start buying other Lehar products. In developing more bottom-of-the-pyramid products PepsiCo says it has seen that rural consumers are not keen to experiment with different tastes. So while Iron Chusti comes with a tangy taste in the south, if it were to be launched in say the north, it would have a more spicy flavour.

Iron Chusti is sold in small towns with a population of less than 2,000 through rural entrepreneurs who go from village to village. Travelling on a bicycle, K. Nagendra covers 18 villages a week. His sole mandate: To get Iron Chusti into as many outlets as possible. He’s paid Rs. 1,500 as a retainer and makes as much as three times more in incentives. “I’m my own boss. I don’t feel like I’m working for anyone,” says Nagendra.

Back in the PepsiCo offices in Gurgaon, Anand is working on creating the same entrepreneurial culture at his Lehar Foods team. For starters, he’s banned PowerPoint presentations at review meetings. Executives are expected to come into his office with their plans on simple work sheets and walk out with clear decisions. Its early days, but Anand says the performance of its bottom-of-the-pyramid businesses have been encouraging. “We’ve got to keep innovating and see what sticks,” he says.