A Business Today article discusses how the growth of Vikram Akula’s SKS microfinance institution, its pursuit of commercial funding, and its initial public offering in 2010, may have been one of the first contributing factors to the microfinance crisis in India today. Some argue that SKS has served as a bad example for other microfinance institutions, which have in turn pursued aggressive growth strategies. Akula, for his part, says that the company’s financials are sound and that only its recoveries in Andhra Pradesh (where the crisis began) are slow. Akula also explains that SKS is implementing pilot projects to gold loans, housing loans, and mobile loans, among other schemes.

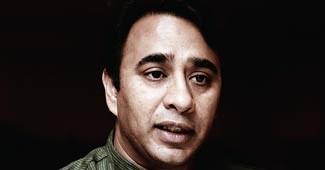

Vikram Akula’s SKS Microfinance , once the showcase company of the Indian microfinance sector, is having to re-design its business as well as salvage its reputation.

Less than a year ago, in August 2010, the company was riding high, having become the first microfinance institution, or MFI, to go in for an initial public offering which was received with much enthusiasm and oversubscribed nearly 14 times. Yet its fourth quarter results, for the year 2010/2011, report a loss of Rs 70 crore.

Worse, its reputation, along with that of the entire microfinance sector, has taken a battering, following suicides by poor borrowers in Andhra Pradesh allegedly due to coercive loan recovery methods resorted to by some MFIs, who had begun to resemble the very village moneylenders they sought to replace.

The Andhra government responded by restricting MFI activities, while the Reserve Bank of India too recently brought in regulations. The forever-clad-in-kurta Akula firmly denies any wrongdoing on SKS’s part. “Whatever happened was due to external factors and was not reflective of any fundamental flaw in our model,” he says. But he has also realised the need to look for new growth avenues. He is considering a four-way diversification of his business. Apart from microfinance, SKS will also provide gold loans (loans against gold), extend housing loans, besides loans to buy mobiles, and to replenish local grocery stores in a supply arrangement with the cash-and-carry chain, Metro. “The pilot projects have been yielding very encouraging results,” he says.

But are external factors solely to blame for SKS’s decline? Not everyone agrees. “The IPO, the firm’s aggressive growth preceding it and the way it attracted others to follow suit laid the road to the current crisis,” says Sanjay Sinha, Managing Director, Micro-Credit Ratings International Ltd, an agency that rates MFIs. In an open letter to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, a World Bank resource agency on microfinance, he wrote: “The success of the IPO itself became a problem, tempting SKS promoters to take ill-timed management decisions, which invited further scrutiny and precipitated the Andhra government’s intervention.”

“SKS was the role model for many MFIs and its aggressive growth encouraged others to scale up similarly. This saw rapid growth with multiple loans to the same borrowers,” says Jayshree Vyas, Managing Director of SEWA Bank, and Chairperson of Sa-Dhan, an association of institutions involved in microfinance.

A look at the financials of 50-odd leading MFIs during the time that SKS began expanding rapidly shows how their yields (the amount realised on average from a client by an MFI) kept falling until 2006 and then began rising fast despite their dipping OER (operating expenses as a proportion of portfolio). Analysts and those like MCRIL’s Sinha link this to SKS’s decision in 2007 to work towards the IPO. “What happened thereafter was that MFIs snapped their relations with the poor borrowers,” says a leading sector expert requesting anonymity.

“There was no social development message, no hand-holding of the poor. It was down to spotting a borrower and engaging in a financial transaction,” says Vijayalakshmi Das, CEO, Ananya Finance for Inclusive Growth, and a respected name in the sector.

Though Akula says SKS’s fundamentals are sound and only recoveries in Andhra Pradesh are a problem following state interference, not many within the sector share his optimism over his company’s balance sheet. The common view seems to be that though SKS was flush with funds following the IPO, what needs to be seen is the way its balance sheet will look three to four years from now. Of the total gross loan portfolio of Rs 4,111 crore, the share of Andhra Pradesh (including the overdues) is Rs 1,285 crore. Even accounting for the 10.3 per cent recoveries continuing in the state, the company’s balance sheet will take a huge hit if SKS writes off such a large amount in the next three to four years. It is these fears that seems to be reflecting on the bourses with the SKS scrip dipping by around 70 per cent since October 2010, when the Andhra government ordinance came in.

But Akula is not unduly fazed – he merely sees the short term as “challenging”, the medium term as “a period of stability”, with a return to robust commercial operations in the long term.

http://businesstoday.intoday.in/story/vikram-akula-sks-microfinance/1/15739.html