Jaipur Rugs, a business that connects local Indian carpet weavers with commercial buyers in the West, continues to grow with rugs worth $32 million in 2011. The business operates an integrated supply chain with approximately 45,000 weavers across 10 Indian states working under contract for Jaipur Rugs. Specifically, it facilitates delivery of raw materials to artisans’ home so that they can work in their villages and has coordinates the collection of finished rugs, which are exported to more than 40 countries. This benefits both weavers who work from their homes and earn a steady income as well as Jaipur Rugs, which receives a steady supply of the product. Jaipur Rugs has a plan to double sales in the US in the next two years and work with 100,000 artisans. The company currently has 1,700 customers in the U.S. and Europe, including large companies such as Crate and Barrel and the Pottery Barn.

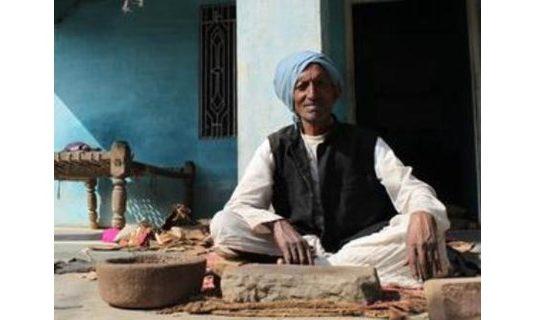

Hunching over a loom for 10 hours a day may not sound pleasant, but for Chottelal it’s a change for the better.

The job means the difference between security and wondering where his family’s next meal will come from.

At his home in the bucolic Indian village of Narhet, he crouches like a baseball catcher on a long board, where he’ll sit for most of the day. He works diligently with his wife, Kanni Devi, who wears a bright orange head covering fringed with white around her face.

They deftly knot maroon yarn around cotton strands suspended from their loom, using metal hand tools to cut and space the knots. In about a month they’ll have a work of commercial art that will end up in a home or hotel halfway across the world.

Before he was a weaver, a traditional industry for this village, Chottelal tried his hand at being a security guard. The job was far away from his three children and didn’t pay well. After six months he lost interest.

He trained for three months to join his wife in the army of more than 45,000 weavers working across 10 Indian states under contract with Jaipur Rugs, a company started more than three decades ago by an entrepreneur who wanted to improve villagers’ lives.

The company now runs on exports to more than 40 countries. It has a showroom at the Americasmart and its American headquarters in Norcross, where recently hired six employees to bring its local total to 30.

An aggressive plan to double sales in the U.S. within two years and reach 100,000 weavers will lead to more jobs for people like Chhotelal and Kanni Devi, who say their futures are brighter thanks to the company. Not only will their children have the option to pursue an education, but they can also afford to have a little fun.

“In our spare time, we take care of livestock and enjoy time with children. We’re going to buy a TV if we can,” the couple told GlobalAtlanta.

People over processes

This family exemplifies what drives N.K. Chaudhary, the founder and chief managing director for Jaipur Rugs.

Long before “social enterprise” was a buzzword, Mr. Chaudhary created his business to fill a need in impoverished rural areas. Rug weavers were being exploited by middlemen who sold their products at a high markup. He sought to reorient the traditional model.

When meeting Mr. Chaudhary, it’s quickly evident that he isn’t your typical chief executive. He removes his shoes in his house. With wide eyes and a pleasant demeanor, he’s humble, quick to listen, and like many Indians, charmingly hospitable. A self-educated businessman, he stresses street smarts over book learning and people over processes, though he knows all are essential to growing his company.

“He’s a true gentleman and a very simple man. To this day he owns two pairs of shoes and 10 shirts,” says Asha Chaudhary, his eldest daughter, a 2001 Emory University graduate in finance and management.

“His passion is people, helping people and growing people, so I really see him as more of a humanitarian,” said Ms. Chaudhary, who is now president and CEO of the U.S. operation.

Mr. Chaudhary went to the state of Gujarat with two looms and built up a network of weavers from poor tribes in the western Indian state.

That was anathema to some in his family, who said working with India’s “untouchable” caste was dangerous, both for his health and his social standing.

“My family members and my parents told me again that tribal people are very bad people and if you go there, they will beat you, they will kill you and they will eat you,” he said.

But he saw potential where others saw lack. Supported by a steadfast wife and influenced by the views of a friend from England, he started training weavers, providing jobs while preserving a traditional art that had begun to fade away.

Mr. Chaudhary never got a business degree, but after many admitted mistakes, he learned how to manage people: Treating them well made them happy, and happy employees were more productive.

“I like people. I love people, so the more people I meet, the more enjoyment I get. If I give them the respect, I will get 10 times more respect,” he told GlobalAtlanta during a wide-ranging interview at his kitchen table in Jaipur, an architectural paradise with beautiful sandstone buildings that have given it the name the Pink City.

The philosophy has paid off. Sales of Jaipur’s handmade woolen and silk rugs were $32 million in 2011 and should eclipse $40 million this year. They have faced competition from machine-made rugs in China, but executives say that upscale retailers will still pay a premium for quality, Jaipur’s competitive advantage.

The human supply chain

In a global market where companies are constantly pressured to drive down labor costs, an integrated supply chain has kept Jaipur Rugs competitive.

“We like to say, ‘We own everything but the sheep,'” Asha Chaudhary says.

But instead of operating massive, centralized factories, Jaipur Rug allows weavers to work in their villages, either in their own homes or with a few co-workers in small production centers with a multiple looms. The company often provides no-interest loans for weavers to buy looms, enabling them to own the means of production.

This army of weavers – 70 percent of whom are women – is overseen by 22 regional offices that send out coordinators responsible for delivering raw materials and collecting finished rugs in each village.

The model benefits every link in the chain: Jaipur gets a steady supply of quality product, while artisans gain a guaranteed customer and avoid hunting down materials. Jaipur also provides loans to help them pay bills while working on complex rug designs that can take months to finish. The company’s foundation also brings free health clinics to villages and trains employees in a variety of skills.

Still, it’s a balancing act between making rugs at a profit while keeping workers happy with their wages. While the weavers interviewed for this story appreciated Mr. Chaudhary’s main innovation – cutting out the middlemen – a few workers were bold enough to lobby for higher rates.

Manni Devi, a recent widow who lost a big chunk of income when her husband died 18 months ago, says she could use a few more rupees to take care of her six children. A spokesperson said she would soon receive extra assistance.

At a group production center in a different part of the village, artisans commend the company while noting their desire for a bigger piece of the pie.

As the forman uses a coded chant to call out each weaver’s next knot, he notes praised the company for giving him job that allows him to stay close to home, but he also points his desire for a raise.

Meena, who estimates her own age to be 35, uses most of her earnings to provide food and education for her three sons and one daughter. She says the rug industry has knitted her community more tightly together at a time when many flee to cities to find jobs.

“It’s a strong bond among us,” she said, flanked by co-workers.

Abhishek Kumar, a spokesman, said requests to raise the rates are common and that the company is always working to strike the right balance between wages and profits.

“We’re always revisiting the rates and trying to address the problem of inflation,” Mr. Kumar said.

Sales here, jobs there

In the Jaipur Rug showroom in Atlanta, Asha Chaudhary bears a clear resemblance to her father.

It’s not just looks; although she thinks about business differently, she carries his vision and aims to infuse it into the company’s operations at a time of mixed messages for luxury goods.

While they have been hit hard over the past few years, discriminating consumers also have a growing appetite for quality products with a social impact.

Jaipur’s feel-good story is becoming a more important part of its sales pitch, but quality is still its main differentiator, Ms. Chaudhary said.

Last year the company had 1,700 different customers across the U.S. and Europe, including retailers like Crate & Barrel and Pottery Barn. Jaipur will target all channels – big-box retailers, online sales, mom-and-pops and high-end boutiques – to reach its goals.

In the end, success with the business processes Mr. Chaudhary lacked when he started the company will help him achieve its raison d’etre.

“We really hope that these add profits and that the growth really helps us take the whole model and make an impact on a much larger number of people than we currently do, Ms. Chaudhary said.

Note: Global Atlanta editor Trevor Williams traveled to India in February and is working on a special report about this emerging market of more than a billion people.

http://www.globalatlanta.com/articlevid/25466/1956/