Through her work at MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, economist Esther Duflo runs randomized, controlled trials to test poverty solutions. In one of her latest trials, Duflo and her team used incentives in villages in rural Rajasthan to see whether that could help increase the number of young children who are vaccinated. Her team tested various incentives through monthly immunization camps in 60 villages. These included employing a nurse and paying her only when her attendance was confirmed, providing famliies a free kilo of lentils whenver families brought children in for shots, and providing them with a set of plates if their children completed a full series of shots. The results showed that despite the cost of giving away free lentils, the additional products incentivized a greater number of families to bring their children to the immunization camps, and therefore reduced the overall cost of providing the immunizations. Despite some controversy over the model, it is encouraging in a country where less than 50% of children receive proper immunization.

Rajasthan is India’s desert state, an often inhospitable place where per capita income averages around $1.77 per day. Poverty like that–understanding it and imagining ways to fix it–is what Esther Duflo lives for. Since 2003, her Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (named for a wealthy Saudi donor), or J-PAL, has conducted 240 randomized, controlled trials of specific ways to help the poor. She tests poverty solutions the way medical researchers test new drugs, which can violate the pieties of the philanthropic community. But she has earned a lot of respect along the way: In 2009, the MIT economist won a MacArthur “genius award” for bringing the scientific method to development work.

In Rajasthan, Duflo has been exploring whether incentives might help get more young children vaccinated. In countries like the U.S., more than 90% of children are immunized. But that’s not the case in the developing world. Some 27 million children around the globe fail to get the shots they need each year; 2 million to 3 million people die as a result. In India, 44% of children get them, but in Rajasthan the official number drops to 22%; in Duflo’s study area near the city of Udaipur, it was less than 2%.

There are several reasons for the low numbers. While the Indian government offers free basic medical care at rural subcenters, government nurses in the area were chronically absent, resulting in clinics padlocked nearly half the time. According to Duflo’s recent book Poor Economics (written with Abhijit Banerjee), there is a cultural resistance to immunization. Superstitions play a powerful role–the “evil eye” is believed to cause illness, and babies are traditionally kept inside for the first year to protect them from it. Furthermore, immunizations have an image problem. When they work, the effect is invisible.

When they don’t seem to work, however, the effects are extremely visible and frightening: The sight of a child made sick by vaccination is terrible, at least in part because it emphasizes how powerless the average person feels in the hands of modern medicine. Rumors of links to autism drove vaccination rates down among rich, educated Americans; not surprisingly, J-PAL found that irrational fears held sway among poor Indians as well.

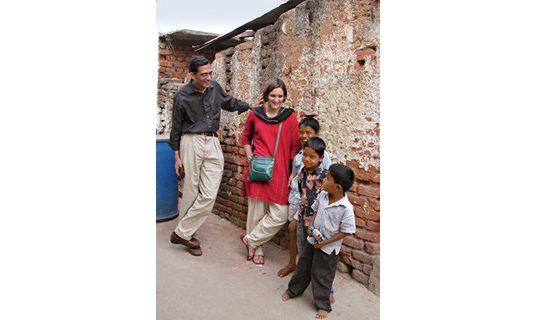

To combat all this, Duflo’s team attempted some simple solutions. “First,” she says, “we wanted to make it easy.” Seva Mandir, a local not-for-profit that partnered with J-PAL, set up monthly immunization camps in 60 villages, each well publicized in the local area and each with a nurse–who was paid only when her attendance was verified. “Second,” Duflo adds, “We wanted to give them a reason to act today, as opposed to waiting one more day.” And that’s where the incentive came in. At half of the immunization camps, researchers gave families a free kilo of lentils every time they brought their child in for shots. If they completed a full series of shots, the family got a set of plates. At the other camps, families only got the shots.

The results were compelling. Simply making shots more available increased the immunization rate from 2% to 18%, according to a survey of households with children aged 1 to 3 years old. But in villages with incentives, the rate jumped to 38%. That’s a great result, of course, but it came with an added benefit. Since so many children showed up, the total cost per immunized child fell by half, despite the $1 bags of lentils that were handed out. Since the nurses were paid by the hour, the busier camps made more efficient use of their time.

So there you have it: a classic win-win, right? Healthier children at cheaper rates. What could be better?

Unfortunately, empirical evidence doesn’t have instant power to convince. “There has been resistance on the left and on the right to the idea of paying people to do the right thing,” says Duflo. “On the left, people say, ‘How can you be so patronizing?’ On the right, they insist that the poor have to be responsible, so we shouldn’t give a handout.” Priyanka Singh, Seva Mandir’s chief executive, says that the approach was initially controversial even within her organization, and points out that other NGOs have also been divided on the issue. The Rajasthani government, after five years of Seva Mandir’s continued success with the model, is still resisting linking immunization to an incentive–even though it offers incentives for family planning and sterilization.

Duflo remains undaunted. “I’m not giving up,” she says. “My day job is to identify good ideas; my night job is to convince policy makers that they are good ideas. That makes for long days!”

Bribing the poor is a notion that could offend just about anyone. We all like our philanthropy pure: Give the money, volunteer at the shelter, act with good intentions, and things will just get better. That’s not a mode of thinking that allows the less fortunate to have human motivations, and it’s certainly not a mode of thinking that encourages us to reflect on our own flaws. But be honest–you’d probably offer your own child a piece of candy as a reward for taking her shots. If we really want to make change, we have to discard what Duflo calls our “cartoon visions” of the poor. Doing good means engaging with what people really need and getting it to them by any means necessary.

http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/158/india-poverty-vaccinations