A New York Times article explores the paradox of India: large cities with shopping malls, luxury stores, and massive apartment towers situated across neighbourhoods with no sewer system, unreliability electricity, garbage on the streets, and people living without proper shelter and sanitation. The city of Gurgaon, near New Delhi, is a case in point, where it has found ways to function despite the lack of public services such as adequate transportation. The idea for how Gurgaon could be developed came about in 1979 when the state of Haryana was split and a Kushal Pal Singh, a real estate developer, began selling its open spaces. Over the next 15 years, Mr. Singh promoted the land among large multinational companies, which have since significantly invested in their operations in the city. However, though the private sector has grown, public infrastructure and services are still dysfunctional.

GURGAON, India — In this city that barely existed two decades ago, there are 26 shopping malls, seven golf courses and luxury shops selling Chanel and Louis Vuitton. Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs shimmer in automobile showrooms. Apartment towers are sprouting like concrete weeds, and a futuristic commercial hub called Cyber City houses many of the world’s most respected corporations.

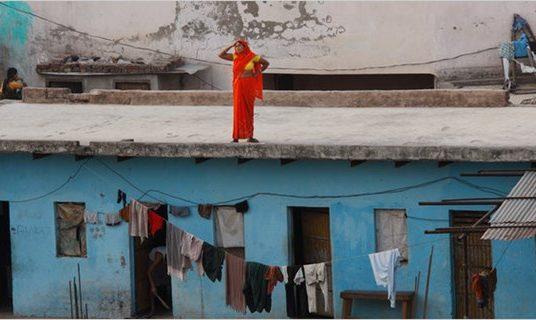

Gurgaon, located about 15 miles south of the national capital, New Delhi, would seem to have everything, except consider what it does not have: a functioning citywide sewer or drainage system; reliable electricity or water; and public sidewalks, adequate parking, decent roads or any citywide system of public transportation. Garbage is still regularly tossed in empty lots by the side of the road.

With its shiny buildings and galloping economy, Gurgaon is often portrayed as a symbol of a rising “new” India, yet it also represents a riddle at the heart of India’s rapid growth: how can a new city become an international economic engine without basic public services? How can a huge country flirt with double-digit growth despite widespread corruption, inefficiency and governmental dysfunction?

In Gurgaon and elsewhere in India, the answer is that growth usually occurs despite the government rather than because of it. India and China are often considered to be the world’s rising economic powers, yet if China’s growth has been led by the state, India’s growth is often impeded by the state. China’s authoritarian leaders have built world-class infrastructure; India’s infrastructure and bureaucracy are both considered woefully outdated.

Yet over the past decade, India has emerged as one of the world’s most important new engines of growth, despite itself. Even now, with its economy feeling the pressure from global inflation and higher interest rates, some economists predict that India will become the world’s third largest economy within 15 years and could much sooner supplant China as the fastest-growing major economy.

Moreover, India’s unorthodox path illustrates, on a grand scale, the struggles of many smaller developing countries to deliver growth despite weak, ineffective governments. Many have tried to emulate China’s top-down economic model, but most are stuck with the Indian reality. In India, Gurgaon epitomizes that reality, managing to be both a complete mess and an economic powerhouse, a microcosm of Indian dynamism and dysfunction.

In Gurgaon, economic growth is often the product of a private sector improvising to overcome the inadequacies of the government.

To compensate for electricity blackouts, Gurgaon’s companies and real estate developers operate massive diesel generators capable of powering small towns. No water? Drill private borewells. No public transportation? Companies employ hundreds of private buses and taxis. Worried about crime? Gurgaon has almost four times as many private security guards as police officers.

“You could call it the United States of Gurgaon,” said Sanjay Kaul, an activist critical of the city’s lack of planning who argues that Gurgaon is a patchwork of private islands more than an interconnected city. “You are on your own.”

Gurgaon is an extreme example, but it is not an exception. In Bangalore, outsourcing companies like Infosys and Wipro transport workers with fleets of buses and use their own power generators to compensate for the weak local infrastructure. Many apartment buildings in Mumbai, the nation’s financial hub, rely on private water tankers. And more than half of urban Indian families pay to send their children to private schools rather than the free government schools, where teachers often do not show up for work.

With 1.2 billion people, India is the largest democracy in the world, a laboratory among developing countries for testing how well democracy is able to accommodate and improve the lives of a huge population. India is richer than ever before, with rising global influence. Yet its development is divisive at home. It is experiencing a Gilded Age of nouveau billionaires while it is cleaved by inequality and plagued in some states by poverty and malnutrition levels rivaling sub-Saharan Africa.

The volatile contradictions of rapid economic growth ricochet daily through Indian life. Middle-class rage over mounting corruption is visceral. Frustration with the government is widespread. Leftists and other critics blame India’s landmark 1991 market reforms for failing to lift the rural poor out of poverty; business leaders warn that India risks slower growth or even stagnation unless those economic changes deepen and governing improves.

Today, Gurgaon is one of India’s fastest-growing districts, having expanded more than 70 percent during the past decade to more than 1.5 million people, larger than most American cities. It accounts for almost half of all revenues for its state, Haryana, and added 50,000 vehicles to the roads last year alone. Real estate values have risen sharply in a city that has become a roaring engine of growth, if also a colossal headache as a place to live and work.

The Birth of a Boom

Before it had malls, a theme park and fancy housing compounds, Gurgaon had blue cows. Or so Kushal Pal Singh was told during the 1970s when he began describing his development vision for Gurgaon. It was a farming village whose name, derived from the Hindu epic the Mahabharata, means “village of the gurus.” It also had wild animals, similar to cows, known for their strangely bluish tint.

“Most people told me I was mad,” Mr. Singh recalled. “People said: ‘Who is going to go there? There are blue cows roaming around.’ ”

Gurgaon was widely regarded as an economic wasteland. In 1979, the state of Haryana created Gurgaon by dividing a longstanding political district on the outskirts of New Delhi. One half would revolve around the city of Faridabad, which had an active municipal government, direct rail access to the capital, fertile farmland and a strong industrial base. The other half, Gurgaon, had rocky soil, no local government, no railway link and almost no industrial base.

As an economic competition, it seemed an unfair fight. And it has been: Gurgaon has won, easily. Faridabad has struggled to catch India’s modernization wave, while Gurgaon’s disadvantages turned out to be advantages, none more important, initially, than the absence of a districtwide government, which meant less red tape capable of choking development.

By 1979, Mr. Singh had taken control of his father-in-law’s real estate company, now known as DLF, at a moment when urban development in India was largely overseen by government agencies. In most states, private developers had little space to operate, but Haryana was an exception. Slowly, Mr. Singh began accumulating 3,500 acres in Gurgaon that he divided into plots and began selling to people unable to afford prices in New Delhi.

Still, growth was slow until after 1991, when the government barely staved off default on foreign debts and began introducing market economic reforms. Demand for housing steadily increased, followed by demand for commercial space as multinational corporations began arriving to take advantage of India’s emerging outsourcing industry.

Outsourcing required workspaces for thousands of white-collar employees. In New Delhi, rents were exorbitant and space was limited, and Mr. Singh began pitching Gurgaon as an alternative. It did have advantages: it was close to the New Delhi airport and a Maruti-Suzuki automobile plant had opened in the 1980s. But Gurgaon still seemed remote and DLF needed a major company to take a risk to locate there.

The answer would be General Electric. Mr. Singh had become the company’s India representative after befriending Jack Welch, then the G.E. chairman. When Mr. Welch decided to outsource some business operations to India, he eventually opened a G.E. office inside a corporate park in Gurgaon in 1997.

“When G.E. came in,” Mr. Singh said, “others followed.”

With other Indian cities also competing for outsourcing business, DLF and other developers raced to capture the market with a helter-skelter building spree. Today, Gurgaon has 30 million square feet of commercial space, a tenfold increase from 2001, even surpassing the total in New Delhi.

“If the buildings were not there,” Mr. Singh said of multinational companies, “they would have gone somewhere else.”

Ordinarily, such a wild building boom would have had to hew to a local government master plan. But Gurgaon did not yet have such a plan, nor did it yet have a districtwide municipal government. Instead, Gurgaon was mostly under state control. Developers built the infrastructure inside their projects, while a state agency, the Haryana Urban Development Authority, or HUDA, was supposed to build the infrastructure binding together the city.

And that is where the problems arose. HUDA and other state agencies could not keep up with the pace of construction. The absence of a local government had helped Gurgaon become a leader of India’s growth boom. But that absence had also created a dysfunctional city. No one was planning at a macro level; every developer pursued his own agenda as more islands sprouted and state agencies struggled to keep pace with growth.

“We have to keep up,” said Nitin Kumar Yadav, the local HUDA administrator. “That is our pressure.”

Gurgaon had been marketed as Millennium City, yet it had become an unmanageable city. For companies that had come to India in search of business efficiencies, the inefficiencies of Gurgaon presented a new challenge they would have to overcome on their own.

Self-Contained Islands

It is 8 p.m. on a recent Tuesday, time for the shift change at Genpact, a descendant of G.E. and one of Gurgaon’s biggest outsourcing companies. Two long rows of white sport utility vehicles, vans and cars are waiting in the parking lot, yellow emergency lights flickering in the early darkness, as employees trickle out of call centers for their ride home. These contracted vehicles represent Genpact’s private fleet, a necessity given the absence of a public transportation system in Gurgaon.

From computerized control rooms, Genpact employees manage 350 private drivers, who travel roughly 60,000 miles every day transporting 10,000 employees. Employees book daily online reservations and receive e-mail or text message “tickets” for their assigned car. In the parking lot, a large L.E.D. screen is posted with rolling lists of cars and their assigned passengers.

And the cars are only the beginning. Faced with regular power failures, Genpact has backup diesel generators capable of producing enough electricity to run the complex for five days (or enough electricity for about 2,000 Indian homes). It has a sewage treatment plant and a post office, which uses only private couriers, since the local postal service is understaffed and unreliable. It has a medical clinic, with a private ambulance, and more than 200 private security guards and five vehicles patrolling the region. It has A.T.M.’s, a cellphone kiosk, a cafeteria and a gym.

“It is a fully finished small city,” said Naveen Puri, a Genpact administrator.

Actually, it is a private island, one of many inside Gurgaon. The city’s residential compounds, especially the luxury developments along golf courses, exist as similarly self-contained entities. Nearly every major outsourcing company in the city depends on private infrastructure, as do the commercial towers filled with other companies.

“We pretty much carry the entire weight of what you would expect many states to do,” said Pramod Bhasin, who this spring stepped down as Genpact’s chief executive. “The problem — a very big problem — is our public services are always lagging a few years behind, but sometimes a decade behind. Our planning processes sometimes exist only on paper.”

For many years, even Gurgaon’s commercial centerpiece, Cyber City, was off the public grid. “They were not connected to any city service,” said Jyoti Sagar, a lawyer and civic activist. “They were like a spaceship. You had these shiny buildings, and underneath you had a huge pit where everybody’s waste was going.”

Not all of the city’s islands are affluent, either. Gurgaon has an estimated 200,000 migrant workers, the so-called floating population, who work on construction sites or as domestic help. Sheikh Hafizuddin, 38, lives in a slum with a few hundred other migrants less than two miles from Cyber City. No more than half the children in the slum attend school, with the rest spending their days playing on the hard-packed dirt of the settlement, where pigs wallow in an open pit of sewage and garbage. Mr. Hafizuddin pays $30 a month for a tiny room. His landlord runs a power line into the slum for electricity and draws water from a borehole on the property.

“Sometimes it works,” Mr. Hafizuddin said. “Sometimes it doesn’t work.”

Even at the fringes of Gurgaon’s affluent areas, large pools of black sewage water are easy to spot. The water supply is vastly inadequate, leaving private companies, developers and residents dependent on borewells that are draining the underground aquifer. Local activists say the water table is falling as much as 10 feet every year.

Meanwhile, with Gurgaon’s understaffed police force outmatched by such a rapidly growing population, some law-and-order responsibilities have been delegated to the private sector. Nearly 12,000 private security guards work in Gurgaon, and many are pressed into directing traffic on major streets.

When an outsourcing employee was sexually assaulted after being dropped near her home in New Delhi, politicians placed the onus on the companies, even though the attack occurred on a New Delhi street. Outsourcing companies now must install GPS devices inside every private car and hire more security guards to escort female employees to their home at night.

The politicians “are basically telling me that the Delhi roads are my responsibility, which is not the case,” said Vidya Srinivasan, who oversees logistics for Genpact.

Yet outsourcing is thriving in Gurgaon, anyway. Last year, a leading Indian industrial association determined that outsourcing was directly and indirectly responsible for about 500,000 jobs in Gurgaon. Companies still gravitate to Gurgaon because the city’s commercial space is more modern, more abundant and far cheaper than that in New Delhi, while Gurgaon is also a magnet for India’s best-educated, English-speaking young professionals, the essential raw material in the outsourcing business. And there is the benefit of a concentration of expertise: in the past decade, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Motorola, Ericsson, Nestle India and other foreign and Indian companies have opened offices in Gurgaon.

Still, Ms. Srinivasan said, the lack of government support is frustrating. She recently returned from a new Genpact operation in the port city of Dalian, China. There, she said, local officials “are doing everything to keep companies like ours.” Asked if the government in Gurgaon was equally responsive, she shook her head.

“In India, it is not because of the government,” she said, explaining how things get done. “It is in spite of the government.”

Playing Catch-Up

Sudhir Rajpal, the wiry, mustachioed commissioner of the new Municipal Corporation of Gurgaon, has a long to-do list: fix the roads, the sewers, the electrical grid, the drainage, the lack of public buses, the lack of water and the lack of planning. The Municipal Corporation was formed in 2008, and Mr. Rajpal, having assumed the city’s top administrative position a few months ago, has been conducting a listening tour to convince people that government can solve their problems.

It is not an easy sell.

One recent morning, his audience was a few dozen farmers in Badshahpur, one of the villages absorbed into the sprawling new territory of the Municipal Corporation. Most are actually former farmers, having sold their land to the developers constructing the office parks and apartment towers now ringing the village. Many of them had bought new cars or new plots of land or invested in the new developments. They were now richer. Their frustration was their village. It was becoming an urban slum.

“The drains are broken and accidents are happening,” shouted one man. “Yet no one is answerable! There are problems and problems. Whatever water we get is dirty, but we have nowhere to complain.”

When India’s public and private sectors are compared, the contrast is usually stark: the private sector is praised for its efficiency, linear command structure and task-oriented ethos; the public sector is condemned for its opacity, lack of accountability and the fact that often no single agency seems in charge. Even as many Gurgaon residents hope that the Municipal Corporation can improve services, others worry that its authority is too limited, given that state agencies will maintain authority over licenses and infrastructure.

In Haryana, developers make campaign donations to politicians and exercise enormous power. Critics say graft and corruption are widespread. Many developers have disregarded promises to construct parks and other amenities. Meanwhile, state agencies like HUDA operate with little accountability. Civic leaders say more than $2 billion in infrastructure fees collected from Gurgaon have gone into HUDA’s general budget without any benefit to the city.

“They used that money somewhere else,” said Sanjeev Ahuja, a veteran journalist in Gurgaon. “The government thinks the private sector will take care of the city: ‘People are rich. If they need water, they can buy water.’ ”

Some people hope Gurgaon’s new municipal council, which was elected on May 13 to oversee the Municipal Corporation, will create a political voice for the city capable of forcing action. Eventually, the Municipal Corporation is expected to assume responsibility for providing services in all of Gurgaon, yet some residents are leery of the change.

Santosh Khosla, an information technology consultant whose family moved to Gurgaon in 1993, has services provided by his developer, DLF. He said DLF had broken numerous promises and did only an adequate job of delivering water and power. Still, adequate is tolerable.

“I’m certain that if it goes to the government,” he said, “it will be worse.”

Citizens Speak Up

Col. Ratan Singh, his military beret placed neatly atop his head, has arrived at a busy intersection in the midday sun for what he calls “an agitation.” He is 82, an Indian Army veteran who has decided that private citizens need to incite a little conflict in Gurgaon. Demonstrations are common in Gurgaon, and he is leading a protest against shoddy work by a contractor.

“Every day some agitation is taking place,” he said, shouting above the din of traffic. “People are not satisfied.”

If people should be satisfied anywhere in India, Gurgaon should be the place. Average incomes rank among the highest in the country. Property values have jumped sharply since the 1990s. Gurgaon’s malls offer many of the country’s best shops and restaurants, while the city’s most exclusive housing enclaves are among the finest in India.

Yet the economic power that growth has delivered to Gurgaon has not been matched by political power. The celebrated middle class created by India’s boom has far less clout at the ballot box than the hundreds of millions of rural peasants struggling to live on $2 a day, given the far larger rural vote, and thus are courted far less by Indian politicians. This has made it harder to accrue the political power needed to correct Gurgaon’s problems. When middle-class civic groups in Gurgaon pushed state leaders to create a single government authority overseeing the city, they were flicked away.

Faced with so many urban headaches, though, civic activists like Colonel Singh are pushing the government for change, or simply making change on their own. Colonel Singh leads an umbrella group of residents’ associations that have started volunteer vigilance groups as watchdogs against crime.

Another civic activist, Latika Thukral, a former Citigroup employee, is involved in creating a biodiversity park. Ms. Thukral led efforts to clean up an illegal garbage dump and is organizing a campaign to plant a million trees this summer.

“If people like us don’t stand up for our rights, our country will not change,” she said. “The tipping point has come in India.”

Across India, Gurgaon is both a model and a cautionary tale. Other cities want to emulate Gurgaon’s growth and dynamism but avoid the dysfunction and lack of planning. Meanwhile, Gurgaon is trying to address its infrastructure woes; last year, the city was connected to the New Delhi rapid transit system, while a public-private project is under way to construct a link to Cyber City. Yet the state and local governments are still struggling to keep up, especially since Gurgaon is already building a industrial district and planning to create more commercial space.

“If Gurgaon had not happened, the rest of India’s development would not have happened, either,” contended Mr. Singh, the chairman of DLF. “Gurgaon became a pacesetter.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/09/world/asia/09gurgaon.html?_r=2&hp